Fast Fish and Loose Fish

In Moby Dick, or the Whale, Ishmael tells us that in whaling, there are fast fish and loose fish.

A fast fish is one that is “connected with an occupied ship or boat, by any medium”—it is made secured and accessible to others.

A loose fish is “a fair game for anybody who can soonest catch it.”

This then lends to a discourse on the legalities of whom can own a fish and what it means to make one fast, and what it means to take possession of something. When I was in university, my Moby Dick professor, K.L. Evans (whose book Whale! is a fascinating look at what it means to make meaning and forge connections, much like a harpoon fastening a fish), taught us to think about writing as fast fish and loose fish, an approach I take to my creative writing.

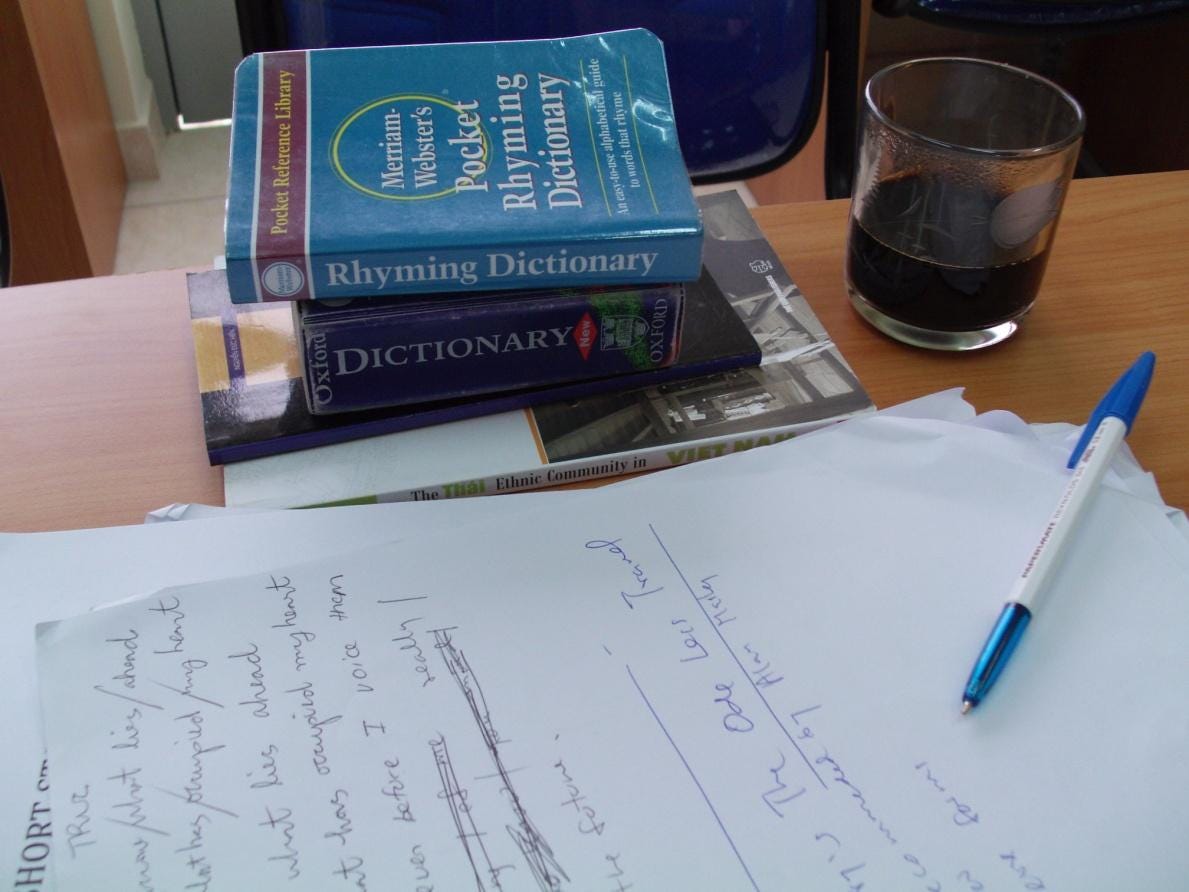

A loose fish is the act of grappling with the idea and putting the words on the paper. I do a lot of “loose fishing” when I’m writing during NaNoWriMo. Getting slightly less than 2k words out a day, between work and child rearing and house owning, often means I have an hour or so to sit down and write. This means I “word vomit.” The ideas are there, the images are in my mind, I have a loose grasp of the words I want to do, and I just write. Setting a sprint helps take what’s in my head and put it out on paper. Otherwise, I will let it fester and bloom and nothing will get done.

But then comes the hard work. We call it editing. I call myself a re-writer. Where I go back to the word vomit, to the loose fish, and I make it fast.

What did I truly mean to say in this moment?

What did I want to convey when Daniel spoke to Tal here? What emotion was I hoping to evoke in the writer? Was there a cleaner, faster way to find this? Where is the flow?

And since I am writing a dual point of view novel, making the writing fast means making sure I’m in the correct voice (Daniel, being highly educated, thinks as the 19th century gentleman that he is; Tal is a rough hewn mortician assistant and she swears. A lot. I love her).

Making a fish fast is a whaler’s work. Making the words fast is the writer’s work. It is often found in chasing again the same white whale. It is often in the work of seeing again, of reading aloud repeatedly, to capture the flow. I find it frustrating when I find myself reworking the same paragraph over and over, but it is in there, that I am doing the work before me of making something fast. So that it sticks to the page, and ideally, to the reader.

It can be as long as a whaling journey, many years at sea, where only inches are covered, and a few thousand words tread. But, as Ishmael tells us “I did not trouble myself with the odd inches; nor, indeed, should inches at all enter into a congenial admeasurement of the whale.”

A novel , a short story, a novella, a poem—whatever you like—is a whale and making it fast cannot be measured in inches, but in the writing sprints which give form and shape to the lives in our head, and the editing, which makes them alive to others.